Velocity-Based Training vs. Linear Speed Development Constructs: A Practical Guide for Coaches Working Along the Force–Velocity Curve

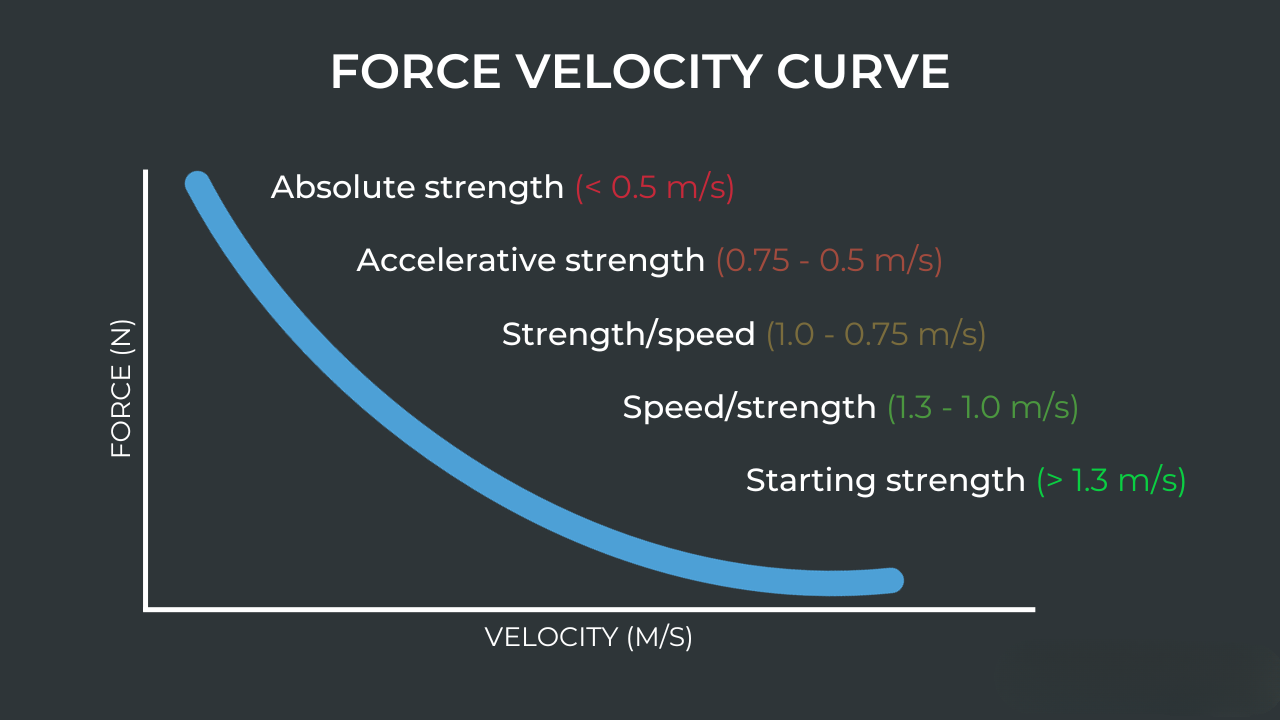

Linear speed is no longer trained by intuition alone. Acceleration, maximal velocity, and speed endurance are governed by distinct neuromuscular qualities, each anchored along the force–velocity (F–V) spectrum. For coaches and clinicians working with competitive athletes, the challenge is no longer what to train — it is how to quantify and progress speed development with precision. The force–velocity curve describes the inverse relationship between force and contraction velocity in muscle. In sprinting and strength training, it becomes a framework for understanding how an athlete produces movement.

Velocity-based training (VBT) has emerged as one of the most powerful tools for solving this problem. When applied correctly, it allows coaches to objectively assess bar or segment velocity under external load (m/s), identify performance bottlenecks, and prescribe targeted interventions that transfer directly to sprint performance. When applied poorly, it becomes another data stream without direction. Real value lies in how coaches interpret and apply the data collected by devices such as the Kinvent K-Power and other similar tech.

Why Linear Speed Must Be Trained Through the Force–Velocity Lens

Linear sprinting is not a single quality. It is an emergent behavior resulting from how an athlete expresses force across time and velocity.Traditional coaching often treats speed development as a universal prescription: more sprints, more drills, more resisted or assisted work — without understanding where the athlete actually needs adaptation.

From a mechanical standpoint:

Early acceleration (0–10 m) is force-dominant

Mid acceleration (10–30 m) reflects a blend of force and velocity

Max velocity (>30 m) is velocity-dominant

Every athlete exists somewhere along this continuum. Two athletes may run the same 40-yard dash time for entirely different reasons:

One may generate exceptional horizontal force but struggle to express velocity.

Another may move quickly but lack the force output to accelerate efficiently.

The Role of Velocity-Based Training in Modern Speed Development

Velocity-based training refers to the use of objective movement velocity data to guide training decisions rather than relying on percentages of max load, subjective observation, or fixed programming templates. In the context of linear speed development, VBT allows coaches to:

Measure how force and velocity are expressed, not just outcomes like sprint time

Track neuromuscular readiness and fatigue

Individualize sprint and strength interventions based on the data collected

Progress athletes with intent rather than volume

This approach aligns with broader trends in emerging rehabilitation and performance technologies — particularly wearable sensors and IMU-based systems — which emphasize ecological validity, real-world data capture, and actionable metrics rather than lab-only diagnostics.

Understanding the Force–Velocity Curve in Practice & Key Profiles Coaches Encounter:

Force-deficient athletes:

Struggle in early acceleration

Slow 5- and 10-yard splits collected by the K-Power

Often rely on high cadence to compensate

Velocity-deficient athletes:

Strong initial push but plateau early

Struggle to reach or sustain top speed

Often overly strength-biased in training history

Well-balanced athletes:

Efficient acceleration and max velocity

Clear transfer between weight room and field

Applying Force Velocity Profiles to Linear Speed Training: Step-by-Step

Step 1: Establish Baseline Sprint Metrics

Using Force–Velocity Profiling for Sprint Acceleration tools (i.e., K-Power) to collect:

Short-distance sprint data (e.g., 5/10/20/30/40 yd splits)

Peak sprint velocity

Velocity–time curves

These metrics reveal:

Acceleration efficiency

Rate of velocity increase

Where velocity plateaus occur

In our NFL Combine Prep environment, this step is critical. Athletes are not trained generically for the 40-yard dash — they are profiled to determine which segment of the sprint limits their performance.

Step 2: Link Sprint Outputs to Strength and Power Expression in the Weight Room via VBT

Sprint performance does not exist independently of the weight room. Velocity-based training allows coaches to connect barbell velocity of squats, jumps, or pulls to (1) sprint velocity during acceleration and (2) power outputs relative to body mass.

If an athlete shows:

Low sprint acceleration velocity + low concentric barbell velocity at moderate loads (<0.5 m/s) - the issue is likely poor force production capacity, not sprint technique.

High force outputs + poor max velocity - may indicate a need for velocity-dominant work rather than additional strength training.

Step 3: Prescribed Training Based on Force–Velocity Deficits:

For force-deficient athletes:

Heavy resisted sprints

Sled pushes with velocity targets

Strength lifts performed in lower velocity zones

Emphasis on horizontal force orientation

For velocity-deficient athletes:

Unresisted or lightly resisted sprints

Assisted sprinting (when appropriate)

Ballistic and elastic strength work

Higher bar velocities with moderate loads

Velocity-based training ensures that intensity stays within the desired velocity bands — preventing strength work from drifting into slow, non-specific adaptations.

Step 4: Monitor Performance Fatigue with the Speed Sensors

During sprint sessions:

Declines in sprint velocity indicate neuromuscular fatigue

Coaches can adjust volume immediately

Quality is preserved over quantity

In strength sessions:

Velocity loss thresholds prevent excessive fatigue

Athletes stay within adaptive zones

Transfer to sprint performance improves

Integrating Force-Velocity Profiles Across Environments

In the Clinic:

Objectively measuring readiness to progress

Quantifying asymmetries post-injury

Supporting return-to-sprint decisions

In the Weight Room:

Load selection becomes dynamic

Daily readiness guides intensity

Strength qualities are trained with sprint transfer in mind

This ensures that weight room work supports (rather than competes with) speed development.

On the Field:

Sprint mechanics are trained at true sprint speeds

Acceleration work remains force-specific

Max velocity work remains elastic and fast

Teaching Athletes to Understand Their Own Profiles

One of the most powerful outcomes of velocity-based training is athlete education. When athletes understand:

Why they are performing certain sprint drills

How force and velocity relate to their performance

What their data indicates about progress

Compliance improves, intent increases, and training quality rises. This is a cornerstone of our approach in elite preparation environments — athletes are not passive participants, but informed collaborators.

Technology as an Enabler, Not the Driver

While hybrid VBT tools such as the K-Power system allow coaches to assess velocity in both sprinting and strength training contexts, the technology itself is secondary to the framework. The best technology is the one that integrates seamlessly into daily practice without disrupting training flow.

Tech integration succeeds when:

Coaches understand the force–velocity curve

Data informs decision-making, not replaces coaching

Metrics are linked to clear training outcomes

Why This Matters for High-Performance Outcomes

At the elite level, marginal gains determine careers. For coaches, therapists, and sport scientists, it represents a shift from training harder to training with intent.

Tech integration provides:

Objective justification for training decisions

Clear documentation of athlete progression

Defensible return-to-performance benchmarks

Improved transfer from the weight room to the field work application

Coaching Along the Curve

Linear speed development is not about choosing the right drill — it is about applying the right stimulus at the right point on the force–velocity curve.

Velocity-based training offers a framework that:

Respects individual athlete needs

Aligns clinic, weight room, and field

Elevates coaching from art alone to applied science

When used correctly, coaches can move beyond guesswork and toward precise performance development.

For those preparing athletes for the highest levels of competition, including the NFL Combine, this approach is no longer progressive — it is foundational.